Lab 4: Text Manipulation

Introduction

In this lab you will perform the following tasks:

-

Edit text files using nano and vi

-

Learn how to work with data streams using pipes and redirection

-

Manipulate command output using common CLI text manipulation utilities

-

Work with filesystem links

-

Search for files

You will be introduced to the following commands:

-

vi

-

nano

-

find

-

ln

-

locate

-

updatedb

-

grep

-

head

-

tail

-

time

Preliminaries

-

Open an SSH remote terminal session to your Linux server’s IP address

-

Connect to ITCnet from the computer you will be using as your administrative PC. In most cases this means connecting to the ITC Student VPN (unless you are using the Netlab Windows Administrative PC).

-

Run the PuTTY software on your computer (or the Windows Administrative PC) and enter in the IP address of your Linux server VM in the "Host Name" box and click the "Open" button.

Remember that if you do not have a Windows computer to connect from you can either figure out how to SSH from your own computer over the VPN to your Linux server or you can use the Windows Administrative PC that is provided for you in Netlab.

-

-

Login with your standard user’s username and password

Text File Editing with vi and nano

|

This section of the lab will explain some things you should try and make sure you can do with |

-

Make sure you are in your regular user’s home directory

-

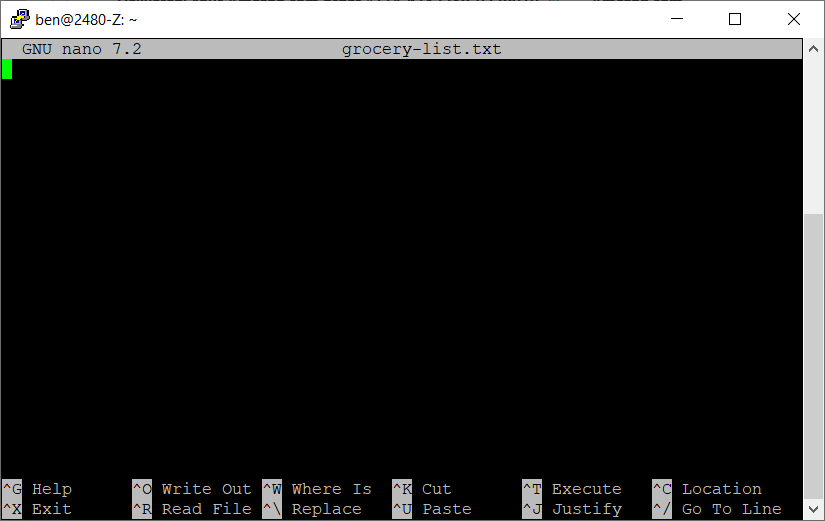

Open a new file named grocery-list.txt in the nano text editor like

nano grocery-list.txtLinux does not require file extensions (the part after the period in a file name) to know what type a file is in the way that Windows/DOS historically have. File extensions are commonly used but are not required. When file extensions are used they can also be more or less than the three letters that are typical on Windows (and required in DOS) so things like .html, .conf, .config, .py, and of course .tar.gz are all examples of commonly found file extensions in Linux. There are also plenty of files you’ll run across in Linux with no file extension at all. This flexibility with file extensions is becoming more common to see in Windows as well but because they were required for so long it’s still less common than in Linux and the defauly in Windows is definitely to have a file extension and usually a three character one.

-

Enter the grocery list below into the file

Groceries: -Apples -Bread -Butter -Eggs -Garlic -Honey -Milk -Onions -Pasta -Peaches -Rice -Salt -TomatoesInstead of re-typing this list if you are using an SSH client on your own computer you can copy and paste this list into the window. You can actually also do this if you’re using the Administrative PC on Netlab but you will need to open this webpage on the Administrative PC because you can’t copy and paste from the computer you are working on into one in Netlab.

We assume you know how to copy text out of your browser window. If you are using PuTTY you can paste into SSH just by right-clicking in the PuTTY window with your mouse and it will paste text just as if you entered it.

If you want to copy text out of PuTTY all you need to do is highlight it with your mouse in the PuTTY window and it immediately is copied onto your clipboard.

-

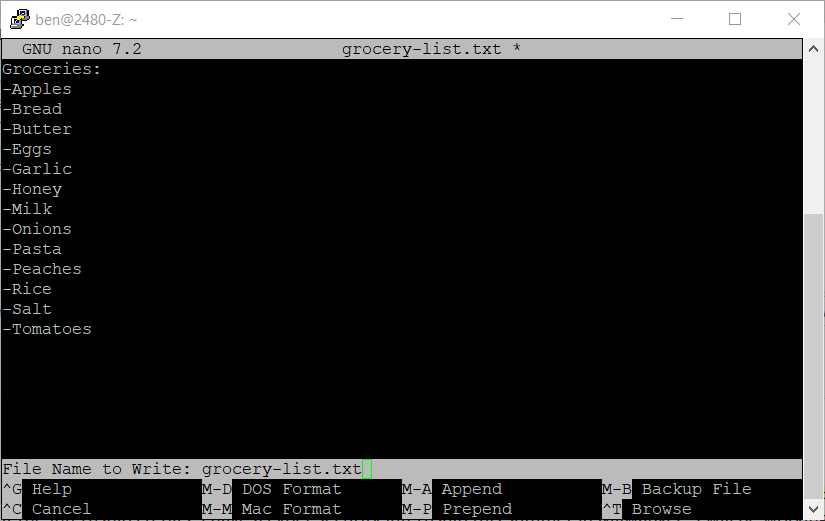

Save the file you have made in nano

-

Basic instructions for using nano abound on the Internet. You can get a basic introduction here but it basically comes down to the menu lines at the bottom of the screen showing what your options are. The

^character is commonly used to indicate the CTRL key. -

Another way to think about saving the file is to write the file to disk so the option to save the file in nano is called "Write Out". Following the above information then, to save the file press CTRL-O.

-

As shown above you will be asked to confirm the "File Name to Write" which will be filled in with the current filename. Because we want to save to the same file we have open we can just press "Enter"

-

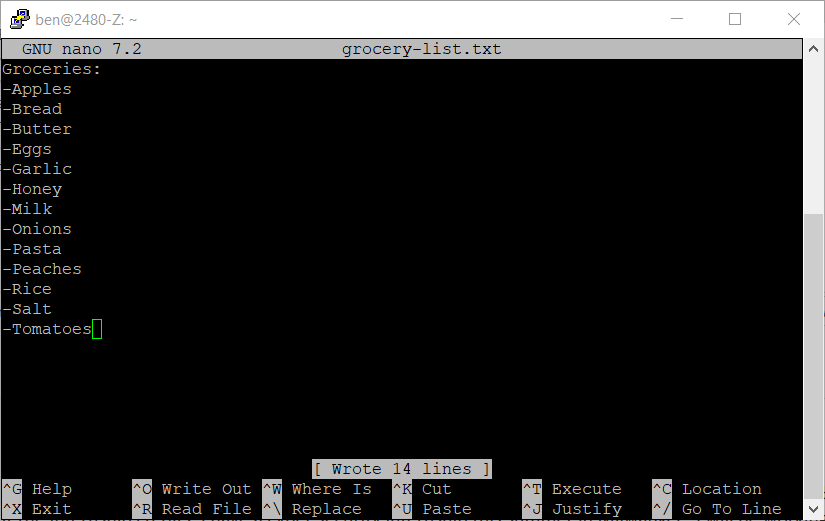

You can see on your screen and in the screenshot above that the save did happen because there is now a line like

[ Wrote 14 lines ]at the bottom of your text editing window.

-

-

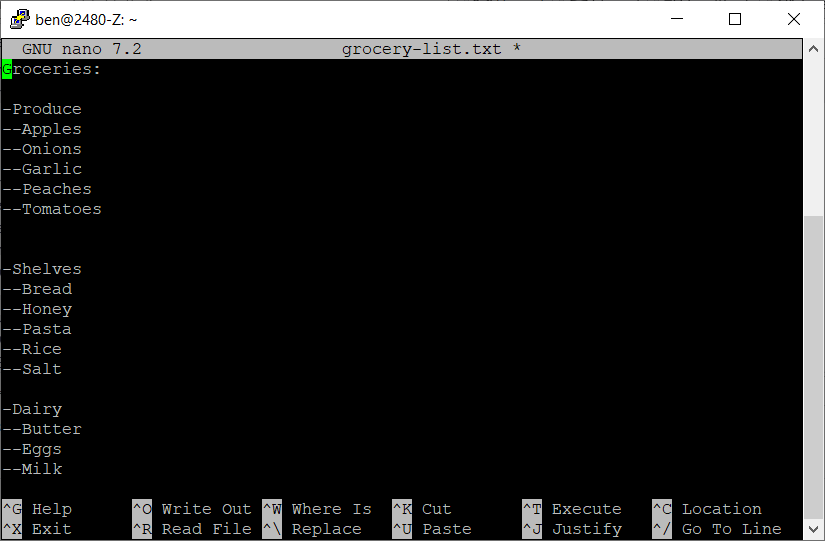

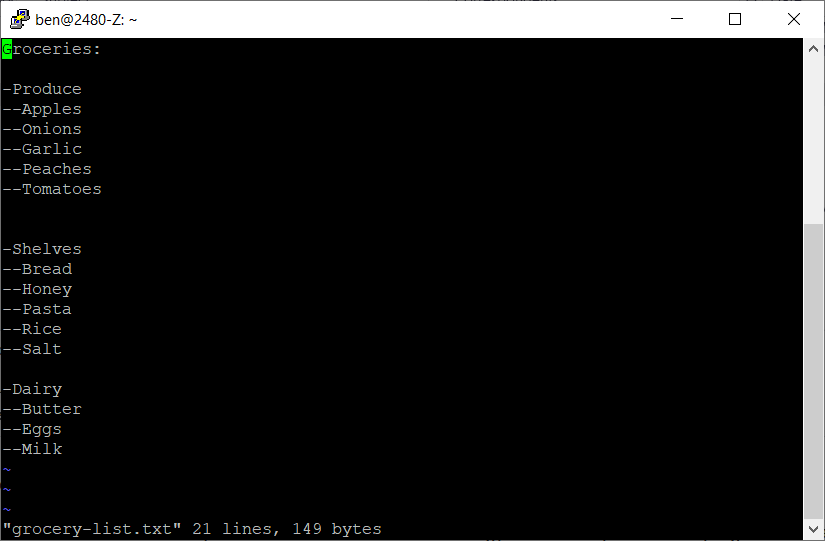

Experiment with some of the other nano menu options such as cutting and "un-cutting" (pasting) lines of text within nano (not by using your mouse) and searching for and replacing text. Make your file look like the example below:

-

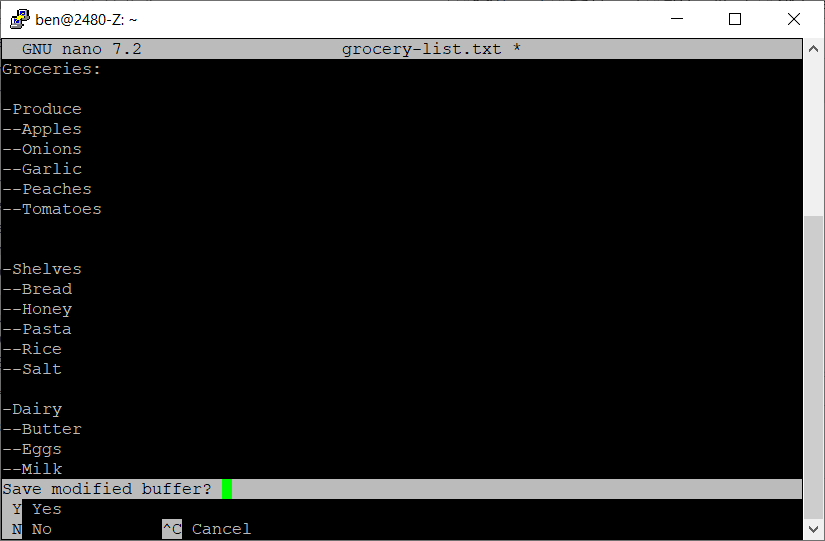

Once you are comfortable with the nano editor exit by pressing CTRL-X. Do this before you save your final changes to the file so you can see that nano will prompt you as shown below:

-

Say "Y" to the question "Save modified buffer?" which means do you want to save your changes before exiting. Again, we want to save with the same grocery-list.txt filename we have been using. You should get returned to the command prompt.

-

Use the

lesscommand to view your grocery-list.txt file and ensure all your changed were saved. -

While the nano editor is pretty user friendly with the menu options on the bottom of every screen it is not always installed on Linux systems. Probably the most standard editor which is almost always available is called

vi. Usually, but not always, it’s actually a version calledvimwhich stands for "vi improved" and has a few features that make it a bit easier to use. That’s a nice thing because the original version of vi can be challenging to work with if you’re not used to it. Because vi/vim are likely to be the only options you have from time to time it’s important to know how to use this editor too. -

Open the grocery-list.txt file in vi like

vi grocery-list.txt. You should be greeted with a sceen like the one shown below:

-

One of the biggest differences with vi is that you cannot just start typing into the editor. In fact, in some versions of vi you cannot even move the cursor around with your arrow keys (old terminal keyboards didn’t have arrow keys so vi has it’s own way to move the cursor). The vi editor has several modes and is in the command mode by default. To type into the window you need to get into insert mode.

-

Move your cursor to where you want to start tying then type the letter

ion your keyboard to enter insert mode. Now you should be able to type something, try it out. -

You may have noticed that in some versions of vi pressing things like your arrow keys while in insert mode will type random characters instead of doing what you want (moving your cursor). Press the Esc key on your keyboard to switch from insert mode back to command mode.

Some versions of vi improved will show you what mode you are in, or at least if you are in insert mode with some text in the lower right corner. Not all versions do this though so you can’t count on it. -

Read through this vi tutorial as well as this one on cutting, copying, and pasting and try out some things on your grocery-list.txt file. At the very least you should have tried and be able to:

-

Insert text

-

Delete characters, words, and lines (and deleteing multiple lines at once)

-

Moving by searching the file

-

Cutting, copying, and pasting one or more lines at a time using the yank, delete, and paste shortcuts

-

Saving the file without closing vi

-

Exiting vi without saving (discarding) any changes

-

Exiting vi and saving changes at the same time

-

The tutorial is actually wrong about this one. For modern versions of vi you type

:wqfrom command mode,zzwill not work.

-

-

-

If you get stuck you can get back to command mode by pressing the Esc key. If you want to get from command mode back to the command prompt (and don’t care about saving any changes) you can always use

:q!and press Enter. -

Once you are familiar with how the vi editor works save your file and exit.

Working With Data Streams Using Pipes and Redirection

When you run a program in Linux it’s likely that you are somehow working with data streams, either providing a stream to the program, getting a stream from the program, or both. Streams can be either text data or binary data (such as audio or video) but the ability to work and manipulate text streams is probably the most common and an important tool for Linux system administrators. As the name implies, a data stream is a continuous flow of data—especially text data—being passed from one file, device, or program to another using STDIO (Standard Input/Output). These streams play a crucial role in the Linux command-line interface. There are three primary streams stdin, stdout, and stderr.

Standard Input (stdin): stdin represents the input stream through which data flows into a command or program. When you interact with a command—whether through the terminal or a script—you’re essentially feeding it data via stdin. Imagine typing a command and pressing Enter; that input travels through stdin. But it’s not limited to keyboard input alone; stdin can also accept data from files, pipes, or other commands.

Standard Output (stdout): stdout is where a command sends its results or regular output. When you run a command and see information displayed in the terminal, that’s stdout at work. It’s the channel through which commands communicate their findings. Like stdin, stdout can carry both text and binary data. For instance, when you list files using the ls command, the file names are sent to stdout or if you are downloading a file with curl it can be sent to the stdout instead of to a file on the filesystem so that it can be further processed by other commands. System administrators rely heavily on stdout for various purposes. They capture output in log files, chain commands together, and monitor processes.

Standard Error (stderr): stderr is the designated channel for error messages, warnings, and diagnostic information. When a command encounters an issue—such as a file not found, a permission error, or an unexpected behavior—it reports relevant details via stderr. System administrators rely on stderr for debugging and troubleshooting. Redirecting stderr to separate log files or to the console while processing stdout spearately allows them to identify and address problems quickly and efficiently by separating errors from normal output.

-

Experiment with redirecting standard output to a file

-

Change back to your regular user’s home directory.

-

List the files in your home directory with all details about size, ownership, and showing hidden files.

-

Now, run the same command but redirect the output to a file by putting

> filenameafter the command likels -al > listfiles.txt.-

Notice how there is no command output. This is normal as you redirected the standard output of the ls ls -al command to the file listfiles.txt

-

-

Verify the contents of listfiles.txt with a command like

cat, orless-

Notice how it contains the exact same output as running ls -al on the command line.

-

-

-

Experiment with redirecting standard output and standard error to different places

-

Still in your home directory use a text editor and paste in this short script to a file named error.sh and save the result

#!/bin/bash echo "We are about to try and access a file that does not really exist" cat doesnotexist.txt -

Set the permissions on the error.sh file so that it can be executed by your regular user like

chmod +x error.sh -

This script does two things when you run it. First, it prints a message stating that it is about to try and access a file that doesn’t exist. This message is sent to the standard output. Second, it tries to use the

catcommand to access a file that does not exist which will generate a standard error message. Try runnung the script like./error.shto see this in action.ben@2480-Z:~$ ./error.sh We are about to try and access a file that does not really exist cat: doesnotexist.txt: No such file or directory ben@2480-Z:~$ -

In this case both the stdout and stderr have been printed to the terminal window as you can see both lines in the example above and in your terminal. Try running

./error.sh > output.txtnow, similar to what you did with thels -alcommand before.ben@2480-Z:~$ ./error.sh > output.txt cat: doesnotexist.txt: No such file or directory ben@2480-Z:~$ -

This time you only get one line of output! It’s the second one, the one that produced a stderr message. You can see what happened to the stdout if you use the

cat stdout.txtcommand to view the output.txt file.ben@2480-Z:~$ ./error.sh > output.txt cat: doesnotexist.txt: No such file or directory ben@2480-Z:~$ cat output.txt We are about to try and access a file that does not really exist ben@2480-Z:~$ -

Here you can see the stdout.txt file contains the first line we would have gotten, the line which was send to the standard output. So the

>operator only redirects the standard output by defauly, not the standard error messages. However, we can redirect the standard output and standard error messages if we want to. Try running./error.sh 2> output.txtthis time and check both what happens on your terminal as well as what ends up in the output.txt file.ben@2480-Z:~$ ./error.sh 2> output.txt We are about to try and access a file that does not really exist ben@2480-Z:~$ cat output.txt cat: doesnotexist.txt: No such file or directory ben@2480-Z:~$ -

As you can see the reverse happened this time, the standard error ended up in the output.txt file and the standard output was printed to the screen. It’s also possible to redirect the output from both the output and error at the same time. Try runing

./error.sh 1> output.txt 2> error.txtand check the screen as well as the contents of both text files.ben@2480-Z:~$ ./error.sh 1> output.txt 2> error.txt ben@2480-Z:~$ cat output.txt We are about to try and access a file that does not really exist ben@2480-Z:~$ cat error.txt cat: doesnotexist.txt: No such file or directory ben@2480-Z:~$ -

Here you can see that nothing was printed to the screen when we ran the command because the standard output message was redirected into output.txt and the standard error message was redirected into error.txt but what if we wanted both in the same file? Try running

./error.sh > output.txt 2>&1and check the screen as well as the contents of output.txt.ben@2480-Z:~$ ./error.sh > output.txt 2>&1 ben@2480-Z:~$ cat output.txt We are about to try and access a file that does not really exist cat: doesnotexist.txt: No such file or directory ben@2480-Z:~$ -

Here you can see that both the standard output and standard error messages ended up in the output.txt file. The

2>&1operator at the end of the command tells the system to take the standard error stream (the>2part as usual) and redirect it back into the standard output stream (the&1part). -

It’s also possible to completely discard one or both of the standard ouput or standard error streams. Try running

./error.sh > /dev/nulland you should see that the standard output just disappears and you are left with only the standard error. If you use /dev/null instead of a filename (for either standard output or error) the system will just immediately discard the stream data.

-

-

Experiment with piping data streams from one application to another and manipulating command output using common CLI text manipulation utilities like

head,tail, andgrep.-

Some programs are able to not only create standard output and standard error streams but also accept input through a standard input stream. This is called piping and uses a special character on your keyboard you have probably not used much before and which is typically called a pipe character in Linux it looks like

|and is typically found on the same key as the backslash\and you press SHIFT + backslash to get the|character. The exact location of this key can vary from keyboard to keyboard but it is most commonly found above the Enter key on modern keyboards. -

Create a text file named linenumbers.txt in your standard user’s home directory with 50 lines in it which are all like "This is Line x" where x is the number of the line.

If you don’t want to use a text editor and do all that typing you can do this easily in Linux using the sequtility which creates a sequence of numbers (see the manual page for more details) and redirection. The commandseq -f 'This is Line %g' 1 50 > linenumbers.txtwill do what we want. -

Check that your linenumbers.txt file is all there with the

catandlesscommands. -

Sometimes we just want to view the beginning or the ending of a file. Luckily, Linux has tools to do just that. The

headandtailcommands allow us to view the first or last 10 lines of a file by default. Try runninghead linenumbers.txtandtail linenumbers.txt. -

We can also change the number of lines from the default of 10 to something else by specifying an option to the command. Try

head -15 linenumbers.txtandtail -5 linenumbers.txt. -

It gets better though. Instead of reading from a file we can use pipes to send standard input to the

headandtailcommands. Trycat linenumbers.txt | head -7to take the standard output from thecatcommand which is reading the linenumbers.txt file and piping it into the standard input of theheadcommand. -

It may not seem that useful yet beacuse we have just replicated functionality that the

headcommand already has built-in. The power is that we can now use this with any other commands which produce standard output. Say we want to get a list of the first 4 files in the directory. Try usingls | head -4to do that. -

We can even combine this with redirection like

ls | head -4 > firstfour.txtTry this and see what happens. -

This can also be useful when working with programs that generate a lot of output. For example, the

dmesgprogram provides a lot information about our system hardware and kernel (we’ll learn more about it later). Try runningsudo dmesg(which requires administrative privileges to run) and watch the text fly by. -

Now, if we wanted to see that information more slowly we could either capture the output to a file and then look through it with

lessor a text editor or we could just pipe the output directly tolesslikesudo dmesg | lesswhich you should now try. Remember that you can scroll up and down with the arrow keys or Page Up/Down keys and press 'q' to exit back to the command line. -

You could also get just the first few lines like

sudo dmesg | head -

When working with a lot of text output it’s also common to be looking for some specific thing. Linux has a tool named

grepwhich allows us to search through text. -

If we were looking for information about our Ethernet network cards we could probably find that in the

dmesgoutput but it could take a long time to look through. If we run the commandsudo dmesg | grep netthough the system can do a lot of work for us. Try running this command and see what you get. -

By default the

grepcommand looks for the text you give it and outputs every full line which contains that text. That is enough to make it very useful but you can do a lot more such as look for patterns (for example any MAC address separated by colons) or strings at the beginning or end of lines using regular expressions. You can learn more about regular expressions at RegexOne and Regular-Expressions.info among many other places. These are frequently used in system administration and programming so it’s worth your while to get at least a basic understanding of them and how they work. -

There are a lot of useful text manipulation commands besides

head,tail, andgrep. You probably even used one,seqto create your linenumbers.txt file. Still others allow further manipulation of text such as searching and replacing text in a data stream withsed,sortto sort lines,cutto send on just a portion of lines,uniqto show lines which are repeated or ignore lines which are repeated, orwcto count words/lines/characters/etc and these are just a few of the many commands available. All of these commands are designed to work with standard input and output to build a chain of commands which does something useful to you. -

Many times this ability to accept standard input is used to process text which was created as an output stream from another program as we did above but it can also be used by programs with binary data. One common use of this is for audio and video encoding where one program might read and decode audio or video data (such as an Audio CD or a WAV file) and pipe that data as standard output over to another program such as an MP3 compression program which compresses the data. That program might write the compressed output to a file or it might send it on to yet another program which streams it out over the network.

-

Working with Filesystem Links

-

The Windows operating system allows you to create "shortcuts" from one file or folder to another and Mac OS allows you to create "aliases" for the same purpose. In much the same way Linux has the ability to create links from one file or directory to another. These can actually be far more powerful than a shortcut or alias though because to almost all applications these links look just like the files or directories are actually located where the link is instead of where the information is actually stored. This means you can use the links in the command line just as you would use the original location.

-

Links in Linux can be either hard links or symbolic links (also called soft links or symlinks). Hard links can only refer to files and need to be on the same drive partition but will follow the file even if it is later moved. Symbolic links are used much more commonly because they can work with directories or files and work across partitions with the only downsides being they will break if the original file/directory is moved or deleted. We’ll focus on using symbolic links because of their additional flexibility and more common use.

-

Create a new directory in you user’s home directory named link-experiments to hold some sample links. There is no requirement that links be in a special directory like this, we’re just doing it in an attempt to keep our home directory a bit organized.

-

Change your working directory to the new link-experiments directory

-

Try creating a new symbolic link named lines.txt and point it to the linenumbers.txt file in your home directory using the

ln -s ~/linenumbers.txt ~/link-experiments/lines.txt -

Try opening the new lines.txt "file" (in quotes because it’s really not a file, it’s a symbolic link to a file) with a text editor. You should see it’s the same as the ~/linenumbers.txt.

-

Make a change to the file and save it.

-

Verify that the change happened in the ~/linenumbers.txt (in other words you were working on a link and not a copy of the file) by looking at it in a text editor

-

You can also see that in a full directory listing of ~/link-experiments/ it is clear that lines.txt is a link and not a file as well as where it points to:

ben@2480-Z:~/link-experiments$ ls -al total 8 drwxr-xr-x 2 ben ben 4096 Aug 16 16:43 . drwx------ 9 ben ben 4096 Aug 16 16:43 .. lrwxrwxrwx 1 ben ben 25 Aug 16 16:40 lines.txt -> /home/ben/linenumbers.txt ben@2480-Z:~/link-experiments$ -

As mentioned before you can link to directories, not only files. Use the

ln -s ~/sample-files/shakespeare ~/link-experiments/shakespearecommand to create a link to your Shakespeare directory. -

Verify the link was created:

ben@2480-Z:~/link-experiments$ ls -al total 8 drwxr-xr-x 2 ben ben 4096 Aug 16 16:46 . drwx------ 9 ben ben 4096 Aug 16 16:43 .. lrwxrwxrwx 1 ben ben 25 Aug 16 16:40 lines.txt -> /home/ben/linenumbers.txt lrwxrwxrwx 1 ben ben 34 Aug 16 16:46 shakespeare -> /home/ben/sample-files/shakespeare ben@2480-Z:~/link-experiments$ -

Try changing your working directory to ~/link-experiments/shakespeare and then listing the files. You should see all the files from your original shakespeare directory (inside sample-files).

-

Note that even if you run

pwdit will look like you are in a sub-directory of link-experiments and not sample-filesben@2480-Z:~/link-experiments/shakespeare$ pwd /home/ben/link-experiments/shakespeare ben@2480-Z:~/link-experiments/shakespeare$ -

Change back to your link-experiments directory.

-

You can create links to other locations on your system as well, not just ones in your home directory. Run the command

ln -s /etc ~/link-experiments/configto create a link called config which points to /etc. -

Links do not allow you to access files you don’t have permission for though just because your user owns the link! Try viewing the ~/link-experiments/config/shadow file with the

catcommand without usingsudo:ben@2480-Z:~/link-experiments$ cat ~/link-experiments/config/shadow cat: /home/ben/link-experiments/config/shadow: Permission denied ben@2480-Z:~/link-experiments$ -

Removing things can also be a little tricky when working with links. If you remove a file inside a linked directory the original file will get removed (assuming you have permissions). Try

rm ~/link-experiments/shakespeare/Sonnets.txt -

Check that the original file is gone with

ls -al ~/sample-files/shakespeare/ -

If a link is to a specific file removing a link itself though does not remove the original file, just the link. The same is true of removing a link to a directory. Run the

rm ~/link-experiments/lines.txtand check that the ~/linenumbers.txt file still exists. Also tryrm ~/link-experiments/configbut see that the /etc directory still exists.As stated above most applications will essentially treat linked things just the same as if the file (or directory) was really in the location where the link is. This is not true in all cases though, applications can tell that it’s a link and decide to handle it differently.

For example, if you are using

tarto back up data, depending on exactly what you want to do you may want to use the-hor--dereferenceoptions to follow symbolic links and backup the data the links point to. Normal behavior fortarwould just be to back up the link itself, not the file(s) or directorie(s) pointed to by the link. See the manual page fortarfor more information.

Searching for Files

There are several ways to search for files on a Linux system. The simplest and the most powerful is to use the find command which searches through the system directory by directory for files which match your search string. You can specify many options for the find command which do things such as restrict to searching in one particular directory and its sub-directories, etc.

-

Try searching your entire drive for files with syslog somewhere in the name.

find / -name "syslog" 2> /dev/nullYour results should look something like those below:ben@2480-Z:~$ find / -name "*syslog*" 2> /dev/null /usr/lib/systemd/system/syslog.socket /usr/lib/modules/6.1.0-18-amd64/kernel/net/netfilter/nf_log_syslog.ko /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/sys/syslog.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/syslog.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog-ldbl.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog-path.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog.ph /usr/share/doc/sudo/examples/syslog.conf /usr/share/doc/busybox/syslog.conf.txt /var/log/installer/syslogYou may have noticed that in the search command we used, find / -name "syslog" 2> /dev/null, we redirected the standard error to the/dev/nulldevice to hide it. The reason we’re redirecting the error messages is that there many files and directories which your regular user may not have permission to access. Each attempt to access these by the find program would create an error message (so lots of errors). We’re basically telling the system to hide these error messages from us. You can see all the errors you would get and how hard it would be to see where these files actually exist by runningfind / -name "syslog" -

You should see some files identified which contain the name syslog. The problem is that the find command is very slow at moving through all the files on the system, in fact it may even appear to be frozen while searching slowly though the drive. This is especially true on systems with a larger number of files on them and/or those that are using spinning hard drives instead of SSDs. If you have waited a while and are still not getting back to a command prompt you can press CTRL-C to force the find program to quit and return to a command prompt.

-

This means the find program works just fine for searching through a few directories/files (such as everything inside your home directory or another smaller part of the system) but is not the best choice for searching the entire system quickly. There are some reasons you may still want to use the find command though such as if you want to search for things other than file name (such as size, permissions, when the file was last changed, etc.) or want to run some command automatically on every file that was found. If you want to learn more about advanced uses of the find command take a look at this tutorial.

-

There is a faster way to search for files on your system with the

locatecommand, but it does have some disadvantages of its own. Locate searches a pre-built database of all files on the system which means it operates much faster than searching though the files themselves one at a time. It also can use regular expressions as part of the search process. There are two main disadvantages though. First, it may not be pre-installed on many Linux systems so you may have to install it. Second, you need to build or update the database before you can search for files (otherwise you would be searching an outdated list of files). New files are not automatically updated to the database so this only really works if you periodically remember to update the database. In future labs we’ll explain how you could schedule the update command to run automatically (hint, see thecronprogram). -

Install the

locateprogram on your system, unlikefindit is usually not installed by default. -

Create an updated database of files on your system by running the

sudo updatedbcommand.In order for the locate database to include all of the files on the system the command to update the database needs permission to read all the files which is why we are running it with administrative permissons. It will take a while for this program to find and index all the files on your system so give it a while to run. The advantage is after you do this you can search the database for many different files very quickly instead of waiting for each search as with the find command. Programs that may need to run for a long time and do not require user input (like updatedb) can be run in the background by placing an ampersand at the end of the command line likesudo updatedb&. This will immediately return you to a command prompt so you can continue to work on other things while the command finishes running. We’ll learn more about background jobs in a future lab. -

Search for files with syslog in the name again but now using the locate database like

locate syslogYour results should look something like those below:ben@2480-Z:~$ locate syslog /usr/lib/modules/6.1.0-18-amd64/kernel/net/netfilter/nf_log_syslog.ko /usr/lib/systemd/system/syslog.socket /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog-ldbl.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog-path.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/sys/syslog.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/syslog.ph /usr/share/doc/busybox/syslog.conf.txt /usr/share/doc/sudo/examples/syslog.conf /var/log/installer/syslog -

Because our virtual machines don’t have too many files on them and are using fast disks you may not notice much speed difference between

findandlocatebut they are there. You can read more about the differences in this StackExchange Q&A or this LinuxConfig article but it’s also possible to see even the small differences yourself. -

If you’re curious how long it takes a command to run in Linux there is an easy way to find out. You can normally just put the command

timein front of whatever command you want to measure and after the command runs you will get a report like this:ben@2480-Z:~$ time find / -name "*syslog*" 2> /dev/null /usr/lib/systemd/system/syslog.socket /usr/lib/modules/6.1.0-18-amd64/kernel/net/netfilter/nf_log_syslog.ko /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/sys/syslog.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/syslog.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog-ldbl.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog-path.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog.ph /usr/share/doc/sudo/examples/syslog.conf /usr/share/doc/busybox/syslog.conf.txt /var/log/installer/syslog real 0m0.515s user 0m0.169s sys 0m0.336s ben@2480-Z:~$ time locate syslog /usr/lib/modules/6.1.0-18-amd64/kernel/net/netfilter/nf_log_syslog.ko /usr/lib/systemd/system/syslog.socket /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog-ldbl.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog-path.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/bits/syslog.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/sys/syslog.ph /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/perl/5.36.0/syslog.ph /usr/share/doc/busybox/syslog.conf.txt /usr/share/doc/sudo/examples/syslog.conf /var/log/installer/syslog real 0m0.022s user 0m0.019s sys 0m0.001s -

In the results above you can see we are given three times for each program, a real, user, and system time. User and sys show how much CPU time the program took to run outside the kernel (in userspace) and inside the kernel. What we’re often most interested in though is how much actual time it took to run a command (as if we had timed it with a stopwatch) which includes any time the system was handling things outside of our program too. That statistic is called the real time. Here you can see that

findtook a little over half a second to run whilelocatetook just over two-tenths of a second to run. In other wordslocatewas just over 23 times faster! While both these results are pretty fast if I run the same two commands on a real-world Linux filesever with a moderate number of files (952,177 compared with 35,526 on our lab systems) find takes 1m53.672s to run while locate completes in 0m0.292s! Now that’s a difference!

Wrapping Up

-

Close the SSH session

-

Type

exitto close the connection while leaving your Linux server VM running.

-

-

If you are using the Administrative PC in Netlab instead of your own computer as the administrative computer you should also shut down that system in the usual way each time you are done with the Netlab system and then end your Netlab Reservation. You should do these steps each time you finish using the adminsitrative PC in future labs as well.

| You can keep your Linux Server running, you do not need to shut it down. |

Document Build Time: 2026-02-20 22:19:49 UTC

Page Version: 2024.01

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License